1. A survey towards consortium-wide conclusions

In order to draw conclusions regarding issues of the greatest importance to the broadest field of Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) research, GP-TCM believed it essential not only to integrate opinions of individual Work Packages (WPs), but also to break the barriers between WPs and even between GP-TCM and the other communities. Based on such considerations, an opinion poll open to all consortium members and non-members was conducted to identify the most important priorities, challenges and opportunities in TCM research. This approach helped us better understand and interpret the major issues, directly or indirectly related to TCM research, both in the view of consortium members and relevant non-members. The survey results have been published in the GP-TCM Journal of Ethnopharmacology Special Issue article (Uzuner et al., 2012). In the following sections, we summarise the survey methodology, outcomes and implications.

Return to top

2. Survey design

The survey was first proposed by the management team of the consortium, according to information and feedback collected from members during the past two years. From June until mid-August 2011, a pre-survey study was conducted amongst all GP-TCM members to identify and accumulate “grand priority”, “grand challenge” and “grand opportunity” candidates. Twenty-five consortium members provided further inputs based on their perspectives, leading to the creation of candidate lists for all the three “grand issues”. Some members argued that, although the primary focus of the survey was TCM research, it would be better to include issues directly related to TCM research and those which could profoundly affect TCM research, e.g. EU-China relations, national and international policies, education, training and qualification of TCM practitioners, etc. Their opinions were adopted so that all nominated items were included in this survey. The study was followed by a full online survey entitled Grand Issues in Traditional Chinese Medicine Research. Consortium members were invited to take part in this anonymous survey. In addition, the survey team contacted 18 national and international societies with various focuses such as TCM, acupuncture, pharmacognosy, complementary medicine and phytochemistry, for their support to circulate the survey amongst their members, of which 13 replied positively (please see the Acknowledgments section for further details).

The invitation email and the online survey were both supplemented with brief information about the consortium and the aims of the survey. The SurveyMonkey website was used to create and host the survey. In addition to the English version, the survey was also translated into Chinese to support Chinese-speaking participants. Preview-mode survey samples in English and Chinese can be viewed below:

Survey sample – English version

Survey sample – Chinese version

The participants were advised that the aim of the survey was to form a consensus on the “grand issues” in the context of the broadest field of TCM research. To achieve this, participants were asked to choose a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 15 from each candidate list to help determine the final list of “top priorities”, “top challenges” and “top opportunities”. An automatic randomisation of candidate items was conducted before every survey to prevent biased choices based on the given orders.

Return to top

3. Outcomes and conclusions of the survey

3.1. Who completed the survey?

A total of 187 questionnaires (156 in English and 31 in Chinese) were completed and analysed. Respondents taking part in the survey were divided into 2 main categories: (a) 77 GP-TCM members, including both beneficiary and non-beneficiary members, accounting for 41% of all participants, and (b) 110 external participants, accounted for 59% of all participants.

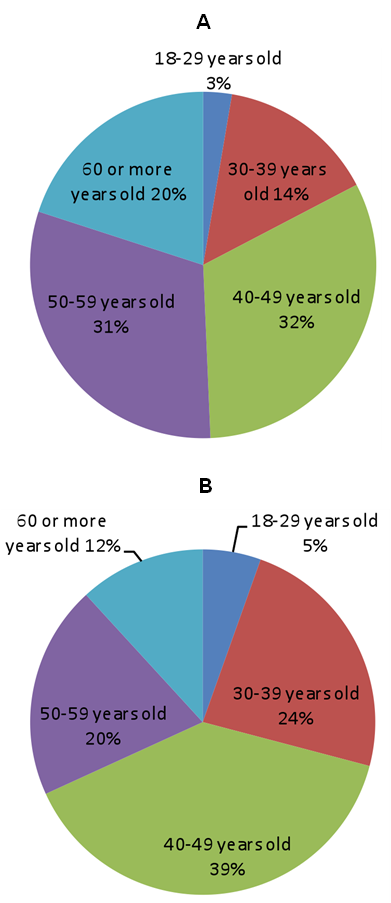

GP-TCM member and external participants both had a gender (female / male) ratio of around 4/6. 52% GP-TCM member participants and 32% external participants were ≥50 years of age (please see Figure 1 below).

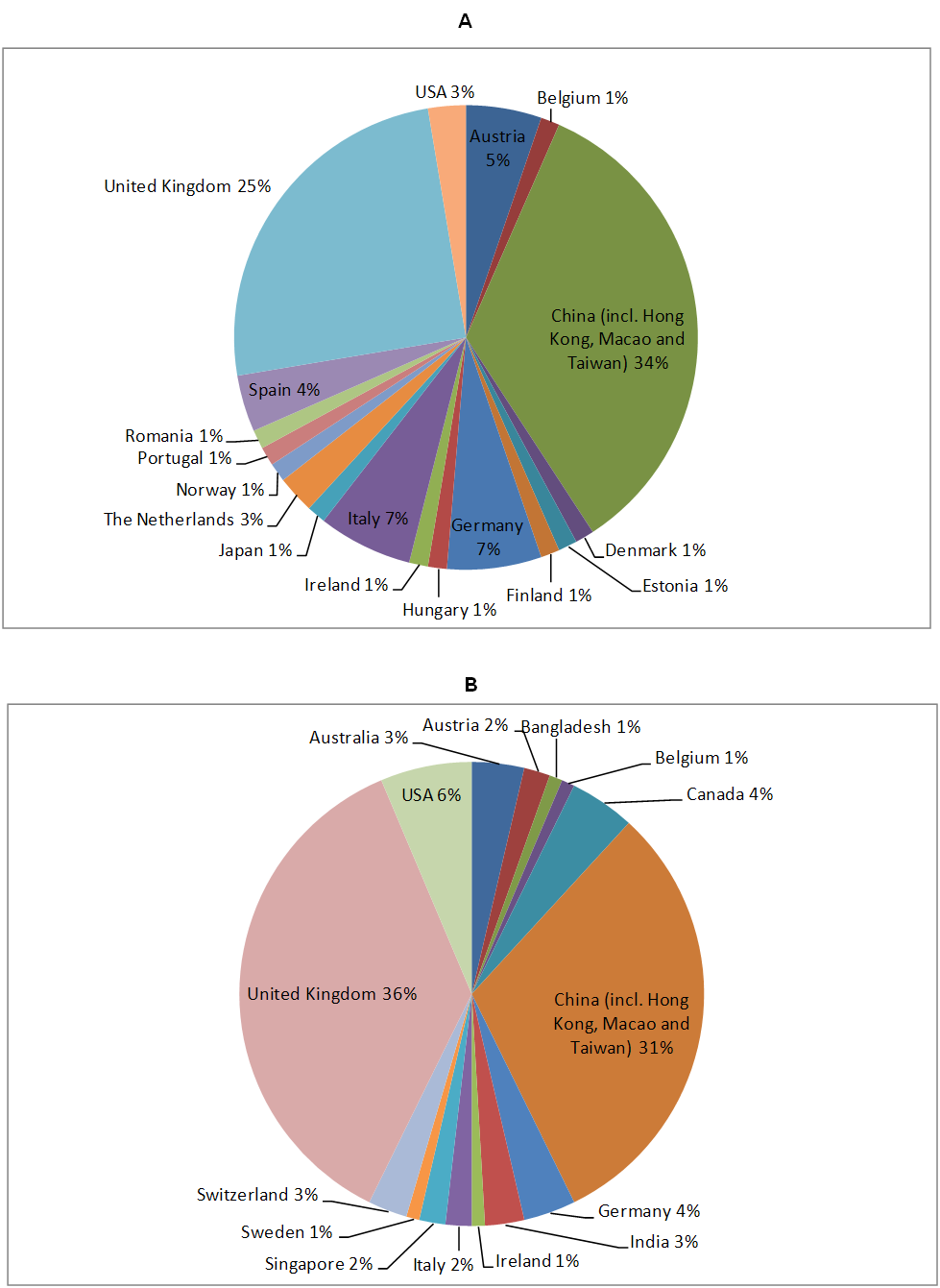

As GP-TCM was mainly an EU-China collaboration, not surprisingly, most GP-TCM member participants were based in either China (34%) or EU member states, including UK (25%), Germany (7%), Italy (7%), Austria (5%), Spain (4%) and the Netherlands (3%). Outside China and the EU, only USA contributed ≥3% of the questionnaires in the group. In contrast, in the external participant group, although China (31%) and two EU member states UK (36%) and Germany (4%) remained main contributors, five countries outside EU and China contributed ≥3% of the questionnaires in the group, including USA (6%), Canada (4%), Australia (3%), India (3%) and Switzerland (3%). Please see Figure 2 for further details.

As GP-TCM was mainly an EU-China collaboration, not surprisingly, most GP-TCM member participants were based in either China (34%) or EU member states, including UK (25%), Germany (7%), Italy (7%), Austria (5%), Spain (4%) and the Netherlands (3%). Outside China and the EU, only USA contributed ≥3% of the questionnaires in the group. In contrast, in the external participant group, although China (31%) and two EU member states UK (36%) and Germany (4%) remained main contributors, five countries outside EU and China contributed ≥3% of the questionnaires in the group, including USA (6%), Canada (4%), Australia (3%), India (3%) and Switzerland (3%). Please see Figure 2 for further details.

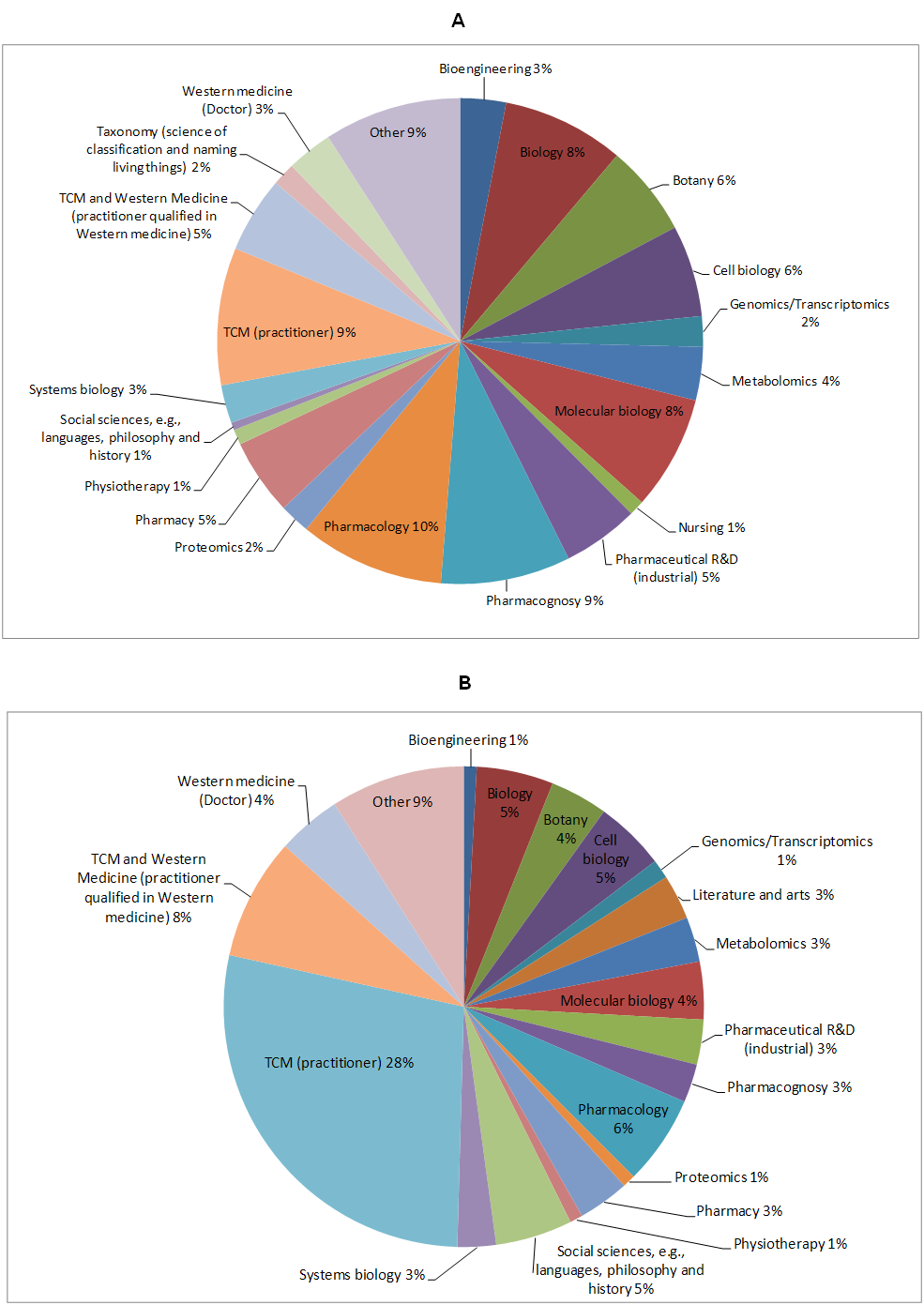

As shown in Figure 3 below, GP-TCM participants were more evenly distributed regarding their expertise and educational background, with experts in pharmacology (10%), TCM, including herbal medicine and acupuncture (9%), pharmacognosy (9%), biology (8%), molecular biology (8%), botany (6%), cell biology (6%), pharmacy (5%), pharmaceutical R&D (5%), TCM and Western medicine (5%), Western medicine (3%), bioengineering 3%, taxonomy (2%), as well as omics technologies, including metabolomics/metabonomics (4%), genomics/transcriptomics (2%), proteomics (2%) and systems biology (3%), etc. These participants were exposed to GP-TCM discussions in the past two years and were familiar with omics and other technologies involved in this survey, even if they were not omics experts. In contrast, distribution of expertise of external participants was less even, with 28% participants being specialised in TCM practice, leading to a possible bias of the view of this group towards the opinions of TCM practitioners. Although 1-4% of external participants claimed omics and/or systems biology background, as a group they would be less familiar with the focused technologies of the GP-TCM consortium, such as omics, because these participants were not exposed to GP-TCM discussions.

As shown in Figure 3 below, GP-TCM participants were more evenly distributed regarding their expertise and educational background, with experts in pharmacology (10%), TCM, including herbal medicine and acupuncture (9%), pharmacognosy (9%), biology (8%), molecular biology (8%), botany (6%), cell biology (6%), pharmacy (5%), pharmaceutical R&D (5%), TCM and Western medicine (5%), Western medicine (3%), bioengineering 3%, taxonomy (2%), as well as omics technologies, including metabolomics/metabonomics (4%), genomics/transcriptomics (2%), proteomics (2%) and systems biology (3%), etc. These participants were exposed to GP-TCM discussions in the past two years and were familiar with omics and other technologies involved in this survey, even if they were not omics experts. In contrast, distribution of expertise of external participants was less even, with 28% participants being specialised in TCM practice, leading to a possible bias of the view of this group towards the opinions of TCM practitioners. Although 1-4% of external participants claimed omics and/or systems biology background, as a group they would be less familiar with the focused technologies of the GP-TCM consortium, such as omics, because these participants were not exposed to GP-TCM discussions.

3.2. Grand priorities, challenges and opportunities

As shown in Tables 1-3, we were able to collect more priority and challenge candidates (N=28 and N=35, respectively) than opportunity candidates (N=18), indicating that TCM research faced more challenges and urgent scientific questions than what could possibly be argued as opportunities. This implied that TCM research remained an emerging area and urgently needed greater support to create more opportunities.

Based on survey outcomes, the grand priorities, challenges and opportunities agreed by at least 50% GP-TCM member and/or external participants are shown in Table 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The tables list grand issues in decreasing order of votes received from GP-TCM members, in comparison to those by external participants. For the full lists of the survey outcomes, please see below the links for the Supplementary tables 1-3.

Table 1. Grand priorities agreed by both GP-TCM members and external participants, or recommended by either GP-TCM members or external participants only

|

Ranking |

Grand Priorities |

|||

|

By GP-TCM Members (N=77) |

By External Participants (N=110) |

|||

| Order | Vote | Order | Vote | |

| Priorities agreed by both GP-TCM members and external participants | ||||

| 2 | 71% | 3 | 60% | High-quality clinical efficacy and effectiveness studies of CHM and acupuncture |

| 3 | 59% | 5 | 56% | High-quality research to demonstrate the mechanisms of action of CHM and acupuncture |

| 3 | 59% | 2 | 60% | Identify priority (disease) areas where TCM is likely to achieve better outcomes for patients and the society |

| Priorities recommended by GP-TCM members only | ||||

| 1 | 72% | 7 | 49% | High-quality research to evaluate the quality and safety of CHM, due to recent and frequent misidentification, adulteration and contamination of CHPs |

| 3 | 59% | 18 | 33% | Taking advantage of the EU-China dialogue channels strengthened through the FP7 GP-TCM Consortium and other consortiums, organisations and societies, develop EU-China joint centres, initiatives and adventures focused on TCM and CMM products |

| 6 | 58% | 11 | 44% | Quality control for those CMMs which were widely used in clinics |

| 7 | 54% | 18 | 33% | Taking advantage of the maturing omics technology and emerging systems biology methodologies, carry out cutting-edge TCM and CHP research |

| 8 | 53% | 15 | 40% | Pharmacovigilance and safety of CMMs |

| 9 | 51% | 12 | 43% | Special attention should be paid to rational use of Chinese medicinal plants, especially those endangered plants, in order to keep sustainable use, maintain biodiversity and protect our environment |

| 10 | 50% | 10 | 45% | Database for compiling all relevant information about TCM. Such a database would provide critical information to interested groups according to a priority topics as well as a tool to centralise all available scientific literature or documents |

| Priorities only recommended by external participants | ||||

| 11 | 49% | 4 | 59% | CHM and acupuncture in prevention and treatment of chronic diseases |

| 12 | 47% | 6 | 55% | Upgraded EU funding and pool funding from a variety of sources to build international research collaborations to support evidence-based clinical and basic research on some maturing areas of TCM, including CMM products |

| 18 | 36% | 1 | 68% | Development of a national policy for TCM supporting the integration of TCM into mainstream health care system, especially in the primary care system. An important requirement is the inclusion of herbal medicine as essential drugs into the health insurance package |

Table 2. Grand challenges agreed by both GP-TCM members and external participants, or recommended by either GP-TCM members or external participants only

|

Ranking |

Grand Challenges |

|||

|

GP-TCM Members (N=77) |

External Participants (N=110) |

|||

| Order | Vote | Order | Vote | |

| Challenges agreed by both GP-TCM members and external participants | ||||

| None | ||||

| Challenges recommended by GP-TCM members only | ||||

| 1 | 63% | 4 | 44% | Quality control of CMMs and CHPs |

| 2 | 51% | 3 | 46% | Lack of European funding for TCM research, compared to the circumstances in China and the USA |

| 3 | 50% | 5 | 43% | Focus on TCM research of certain chronic diseases and conditions, where TCM has established a good track record of clinical efficacy by using scientific methods to provide scientific evidence for efficacy |

| 3 | 50% | 23 | 26% | Pharmacovigilance of CHPs |

| Challenges only agreed by external participants | ||||

| 13 | 36% | 1 | 51% | Regulation of TCM practitioners in the EU |

Table 3. Grand opportunities agreed by both GP-TCM members and external participants, or recommended by either GP-TCM members or external participants only

|

Ranking |

Grand Opportunities |

|||

|

By GP-TCM Members (N=77) |

By External Participants (N=110) |

|||

| Order | Vote | Order | Vote | |

| Opportunities agreed by both GP-TCM members and external participants | ||||

| 1 | 75% | 1 | 82% | Long-term conditions and chronic diseases are top challenges for Europe and TCM might offer potentially useful knowledge on these diseases and conditions, including ageing, infectious disease, diabetes and obesity |

| 3 | 55% | 4 | 57% | Potentially positive or negative effects of drug combinations from both systems needs to be established |

| 4 | 54% | 3 | 60% | Openness and readiness for EU and China to jointly fund clinical studies including trials and observational studies in both countries/locations |

| 6 | 53% | 6 | 51% | Chinese government recently announced a $308 billion biotech industry expansion scheme to create one million new biotech jobs in 2015. EU has to come up with new policy and funding initiatives to promote biotech industry especially TCM or herbal medicine projects to attract Chinese partners and investments |

| 9 | 50% | 2 | 64% | Knowledge accumulated through thousands of years of TCM clinical experience provides rich resources for knowledge transfer/education and for understanding and integration of Western and Eastern ideals. The knowledge transfer should eventually benefit healthcare and pharmaceutical industry and education should not be restricted to scientists, it should include industry, the regulators, charities and the public |

| Opportunities recommended by GP-TCM members only | ||||

| 2 | 57% | 16 | 37% | Maturing omics and improving systems biology methodologies have offered powerful tools to interpret the complexity and holism of CMM and TCM |

| 4 | 54% | 18 | 28% | With the FP7 GP-TCM funding, an EU-China collaborating forum has been established and good practice guidelines have started to be developed |

| 6 | 53% | 8 | 45% | Bridging the gap between modern personalised health (including sub-health condition) and personalised TCM diagnosis and treatment using omics and systems biology |

| 8 | 51% | 17 | 33% | Network based pharmacological evaluation for CMMs |

| 9 | 50% | 14 | 39% | China’s open policy and ever increasing funding to scientists in China create good collaborating opportunities |

| Opportunities recommended by external participants only | ||||

| 11 | 49% | 5 | 55% | International cooperation on clinical trial for marketed CMMs |

3.3. Data interpretation

General conclusions

Both the GP-TCM member group and the external participant group agreed on five grand opportunities, three grand priorities, but interestingly, these two groups did not have any consensus on grand challenges.

GP-TCM member participants tended to achieve more consensus than the external participants did. In addition to the three grand priorities agreed by both groups of participants, GP-TCM members agreed on seven more priorities and external participants agreed on an additional three items. Although the two groups did not achieve consensus on grand challenges, GP-TCM member participants did agree on four grand challenges, but external participants agreed on only one. Finally, besides the five grand opportunities agreed by both groups, GP-TCM members agreed on additional five but external participants agreed on only one. This could be explained by the fact that GP-TCM member participants were a more balanced group that were more familiar with the specific research area, for which consensus was easier to be achieved. In this regard, the GP-TCM had achieved one of its objectives, i.e. to find common ground for this emerging area through building and training a balanced team, facilitating networking, learning and discussion in order to increase consensus, while respecting differences.

The opinions of these two groups varied mainly at the following aspects: (i) any items involving specialist terms, which were not explained in detail in the survey, such as “omics”, “pharmacovigilance”, “GP-TCM” were ranked highly among GP-TCM member participants, but not by the external participants. This is to be expected since people could not vote for things that they were not familiar to, because they did not know if they were important or not; (ii) GP-TCM members’ ranking gave more attention to items related to research, because GP-TCM is a consortium focused on TCM research; (iii) external members voted for research but also highly ranked items that were not directly related to research but nevertheless would also affect research indirectly. This was because we asked participants to vote for “grand issues” of greatest importance to TCM research, directly or indirectly. Thus, opinions from external participants should serve as an excellent complement to the views of consortium members. Views of the two groups should both be given serious consideration in the future.

What was agreed by both GP-TCM member and external participants?

As shown in Table 1, both groups agreed that high-quality research on efficacy/effectiveness and mechanisms of action of CHM and acupuncture, as well as identification of priority disease areas where TCM could achieve better outcomes were grand priorities. These results indicated that there was a clear consensus on the need to acquire high-quality evidence to conclude on if and how TCM could offer benefits.

The lack of consensus between the two groups on grand challenges was one of the most intriguing findings of this survey. This implied that, although the GP-TCM consortium could recommend grand challenges, it would take efforts to disseminate, interpret the recommendations, collect feedback and make refinements in order to increase consensus and unite more stakeholders to tackle these challenges together.

While both groups generally agreed that TCM knowledge offered grand opportunities, they further agreed that the top opportunity was likely offered by TCM contribution to the management of one of EU’s top healthcare challenges, i.e. long-term conditions and chronic diseases (Table 3). They also agreed that combined use of drugs from both TCM and Western medicine and the recent huge funding to support TCM and biotech research in China should offer opportunities. In particular, openness and readiness for EU and China to jointly fund clinical studies were singled out as an opportunity to watch.

What was agreed by GP-TCM members only?

As shown in Table 1, the consensus of the two groups on the need for high-quality research on efficacy and mechanisms of action of TCM was logically linked to two grand priorities agreed by the GP-TCM member group, i.e. “developing EU-China joint centres, initiatives and adventures focused on TCM and CMMs” and “cutting edge TCM and CHP research using omics and systems biology technology”. These could be interpreted as the answers from the consortium on how high-quality research on efficacy and mechanisms could be achieved. Interestingly, three quality- and safety-related issues, i.e. “high-quality research to evaluate the quality and safety of CHM” and “quality control for commonly used CMMs” and “pharmacovigilance and safety of CMMs” were prioritised by GP-TCM member participants, but were only moderately voted by external participants. These discrepancies reflected the emphasis of the GP-TCM consortium on quality of CMMs and their safe use, in spite of the general confidence of TCM practitioners and relevant stakeholders in the clinical safety profile of CMMs. Of note, the toxicology work package of the GP-TCM consortium (WP3) especially focused on chronic toxicity, which might not be readily noticeable by TCM practitioners but could be identified by systemic clinical pharmacovigilance (Ouedraogo et al., 2012; Shaw et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). 50%-51% GP-TCM member participants also emphasised the importance of rational use of medicinal plants and constructing a comprehensive TCM literature database, which were supported by slightly fewer than half external participants (43%-45%).

For GP-TCM member participants, quality control of CMMs and CHPs and pharmacovigilance of CHPs were not only grand priorities but also grand challenges. Quality control of CMMs and CHPs posed a grand challenge thanks to their complexity, which made them unsuitable for quality assurance by methodologies used for conventional drugs. Clinical pharmacovigilance of CHPs also posed as a grand challenge as it needed a fully functioning adverse event report network, qualified experts and funding for data integration and analysis, which were not fully established yet worldwide, as reviewed by WP3 (Shaw et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). TCM management of chronic diseases, a grand opportunity agreed by both groups, was also regarded a grand challenge by GP-TCM member participants, because efficacy studies of CMM/CHP in chronic diseases usually needed long duration of observation and there were still many unsolved problems in clinical trials of CHM and CHPs, including decoctions and granules (Flower et al., 2012; Luo et al., 2012). Noticeably, lack of European funding for TCM research was singled out as a grand challenge for the European TCM scientific community as there was no funding yet dedicated to TCM research in Europe, in contrast to the federal funding dedicated to research of complementary medicines (including TCM) by the US National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicines, and the rich, still rapidly increasing, funding into TCM research by a number of mainstream Chinese funders.

GP-TCM member participants voted confidence in maturing omics and improving systems biology methodologies as powerful tools to interpret the complexity and holism of CMM and TCM, as well as bridging TCM with modern personalised health. This confidence was based on their literature analyses on the state of the art of omics studies of in-vitro and in-vivo pharmacology (Buriani et al., 2012), regulatory science (Pelkonen et al., 2012) and acupuncture (Jia et al., 2012). GP-TCM member participants also voted confidence in the opportunities offered by the collaboration forum and good practice guidelines established by the GP-TCM consortium and this confidence was clearly encouraging and required for the healthy development of TCM research in Europe. In addition, GP-TCM member participants ranked network based pharmacological evaluation (i.e. network pharmacology) (Hopkins, 2008; Ainsworth, 2011) and China’s open policy and increasing funding in China grand opportunities, as these would offer new research strategies and create even stronger collaborators.

What was agreed by external participants only?

As shown in Table 1, external participants gave top priority to “support integrating TCM into mainstream health care system”, with 67.6% vote of confidence as a grand priority. In contrast, this item only attracted votes from 34.7% GP-TCM member participants. This might reflect the gap between the wish of many TCM practitioners, who were the largest subgroup among external participants, and the more objective and realistic votes by scientists, who comprised the biggest part in the GP-TCM consortium. Echoing GP-TCM’s appeal for the challenges posed by lack of funding in Europe, external participants also acknowledged the importance of funding in TCM research, regarding it as a priority to pool funding from various sources to support international collaborations. Echoing the agreement by both groups on TCM treatment of chronic diseases as a grand opportunity TCM could offer (Table 1), 59% external participants and slightly fewer than half GP-TCM member participants (49%) also recommended TCM treatment of chronic diseases as a priority for future TCM research. Similarly, “international cooperation on clinical trials for marketed CMMs” received 55% of vote from external participants, while slightly fewer than half GP-TCM member participants (49%) recommended this item as an opportunity for future TCM research.

External participants did not achieve much consensus on what were the grand challenges in TCM research. Only “regulation of TCM practitioners in the EU” received more than half votes (51%) and became the only grand challenge agreed by this group. As regulation of CHP had recently been updated (Fan et al., 2012), regulation of practitioners clearly would have a profound impact on the TCM industry and also indirectly on TCM research.

Return to top

4. Conclusions

Through an online survey open to GP-TCM members and non-members, we polled opinions on grand priorities, challenges and opportunities in TCM research. Based on the poll, although consortium members and non-members had diverse opinions on the major challenges in the field, both groups agreed that high-quality efficacy/effectiveness and mechanistic studies are grand priorities and that the TCM legacy in general and its management of chronic diseases in particular represent grand opportunities. Consortium members cast their votes of confidence in omics and systems biology approaches to TCM research and believed that quality and pharmacovigilance of TCM products are not only grand priorities, but also grand challenges. Non-members, however, gave priority to integrative medicine, concerned on the impact of regulation of TCM practitioners and emphasised intersectoral collaborations in funding TCM research, especially clinical trials.

The GP-TCM consortium made great efforts to address some fundamental issues in TCM research, including developing guidelines, as well as identifying priorities, challenges and opportunities. These consortium guidelines and consensus will need dissemination, validation and further development through continued interregional, interdisciplinary and intersectoral collaborations. To promote this, a new consortium, known as the GP-TCM Research Association (http://project.gp-tcm.org/association/), has been established to succeed the 3.5 year fixed term 7th Framework Programme (FP7) GP-TCM consortium and was officially launched at the Final GP-TCM Congress in Leiden, the Netherlands, on 16th April 2012.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jue Zhou (Zhejiang Gongshang University, China) and Dr. Fan Qu (Zhejiang University, China) for translating the “GP-TCM Grand Issues” survey into Chinese.

We sincerely thank all sister societies, consortia and stakeholders that have supported us in the preparation and distribution of this survey. In particular, the following organisations are sincerely acknowledged for distributing, and encouraging their members to complete, the “Grand Issues” survey: The American Society for Pharmacognosy; Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, UK; The British Acupuncture Council; Consortium for Globalisation for Chinese Medicine; Deutsche Ärztegesellschaft für Akupunktur/German Medical Acupuncture Association, Germany; Deutsch-chinesische forschungsgemeinschaft für TCM, Germany; Federation of Traditional Chinese Medicine, UK; The International Association for the Study of Traditional Asian Medicine; International Council of Medical Acupuncture and Related Techniques; Research Council for Complementary Medicine, UK; The Society for Medicinal Plant and Natural Product Research; TCM initiative Köln, Germany; and The Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners UK.

References

Ainsworth, C, 2011, Networking for new drugs. Nature Medicine. 17, 1166-1168.

Buriani, A., Garcia-Bermejo, M.L., Bosisio, E., Xu, Q., Li, H., Dong, X., Simmonds, M.S.J., Carrara, M.,Tejedor, N., Lucio-Cazana, J., Hylands, P.J., 2012. Omic techniques in systems biology approaches to traditional Chinese medicine research: present and future. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 535-544.

Fan, T.-P., Deal, G., Koo, H.-L., Rees, D., Svedlund, L., Chen, S., Dou, J.-H., Makarov, V.G., Pozharitskaya, O.N., Shikov, A.N., Kim, Y.S., Huang, Y.-T., Chang, Y.S., Jia, W., Dias, A., Chan, K., 2012. Future development of global regulations of Chinese herbal products. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 568-586.

Flower, A., Witt, C., Liu, J.P., Ulrich-Merzenich, G., Yu, H., and Lewith, G., 2012. Guidelines for randomized controlled trials investigating Chinese herbal medicine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 550-554.

Hopkins, A.L., 2008, Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery. Nature Chemical Biology. 4, 682-690.

Jia, J., Yu, Y., Deng, J.-H., Robinson, N., Bovey, M., Cui, Y.-H., Liu, H.-R., Ding, W., Wu, H.-G., Wang, X.-M., 2012. A review of Omics research in acupuncture: the relevance and future prospects for understanding the nature of meridians and acupoints. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 594-603.

Luo, H., Li, Q., Flower, A., Lewith, G., Liu, J., 2012. Comparison of effectiveness and safety between granules and decoction of Chinese herbal medicine: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 555-567.

Ouedraogo, M., Baudoux, T., Stévigny, C., Nortier, J., Colet, J.-M., Efferth, T., Qu, F., Zhou, J., Chan, K., Shaw, D., Pelkonen, O., Duez, P., 2012. Review of current and “omics” methods for assessing the toxicity (genotoxicity, teratogenicity and nephrotoxicity) of herbal medicines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 492-512.

Pelkonen, O., Pasanen, M., Lindon, J.C., Chan, K., Zhao, L., Deal, G.,Xu, Q., Fan, T.-P., 2012. Omics and its potential impact on R&D and regulation of complex herbal products. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 587-593.

Shaw, D., Ladds, G., Duez, P., Williamson E., Chan, K., 2012. Pharmacovigilance of herbal medicines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 513-518.

Uzuner, H., Bauer, R., Fan T.-P., Guo, D., Dias, A., El-Nezami, H., Efferth, T., Williamson, E.M., Heinrich, M., Robinson, N., Hylands, P.J., Hendry, B.M, Cheng, Y.C., Xu, Q., 2012. Traditional Chinese medicine research in the post-genomic era: Good practice, priorities, challenges and opportunities. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 458-468.

Zhang, L., Yan, J., Liu, X., Ye, Z., Yan, X., Meyboom, R.H.B., Chan, K., Shaw, D., Duez, P., 2012. Pharmacovigilance practice and risk control of traditional Chinese medicine drugs in China: Current status and future perspective. Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2012), 140: 519-525.

Return to top

Return to top